Neuroscience - Cocaine's Control Flow Hijack of Dopamine Circuits

Cocaine - Introduction

Cocaine is a psychoactive drug originating in South America and distributed worldwide.

It has gained significant popularity, particularly across Western societies, where it is one of the most commonly used stimulants.

In Europe, cocaine ranks as the second most frequently consumed illicit drug, with usage patterns dominated by males. Its high addictive potential stems from the way it hijacks our reward systems: repeated exposure conditions the brain toward compulsive use, gradually eroding conscious control and decision-making around consumption.

The health consequences are severe, ranging from agitation, psychosis, and cardiovascular strain (tachycardia, hypertension, arrhythmia) to acute coronary syndrome and stroke.

Cocaine - Synaptic Hijack

I described in my first post the fundamental principles of synaptic transmission.

In this post, we dive into cocaine’s function and how it interferes with the dopaminergic system.

As one review put it, “Early rudiments [dopamine pathways] are found in worms and flies, which take us back 2 billion years in evolution.”1

This highlights how cocaine impacts circuits deeply rooted in systems that are fundamental for survival.

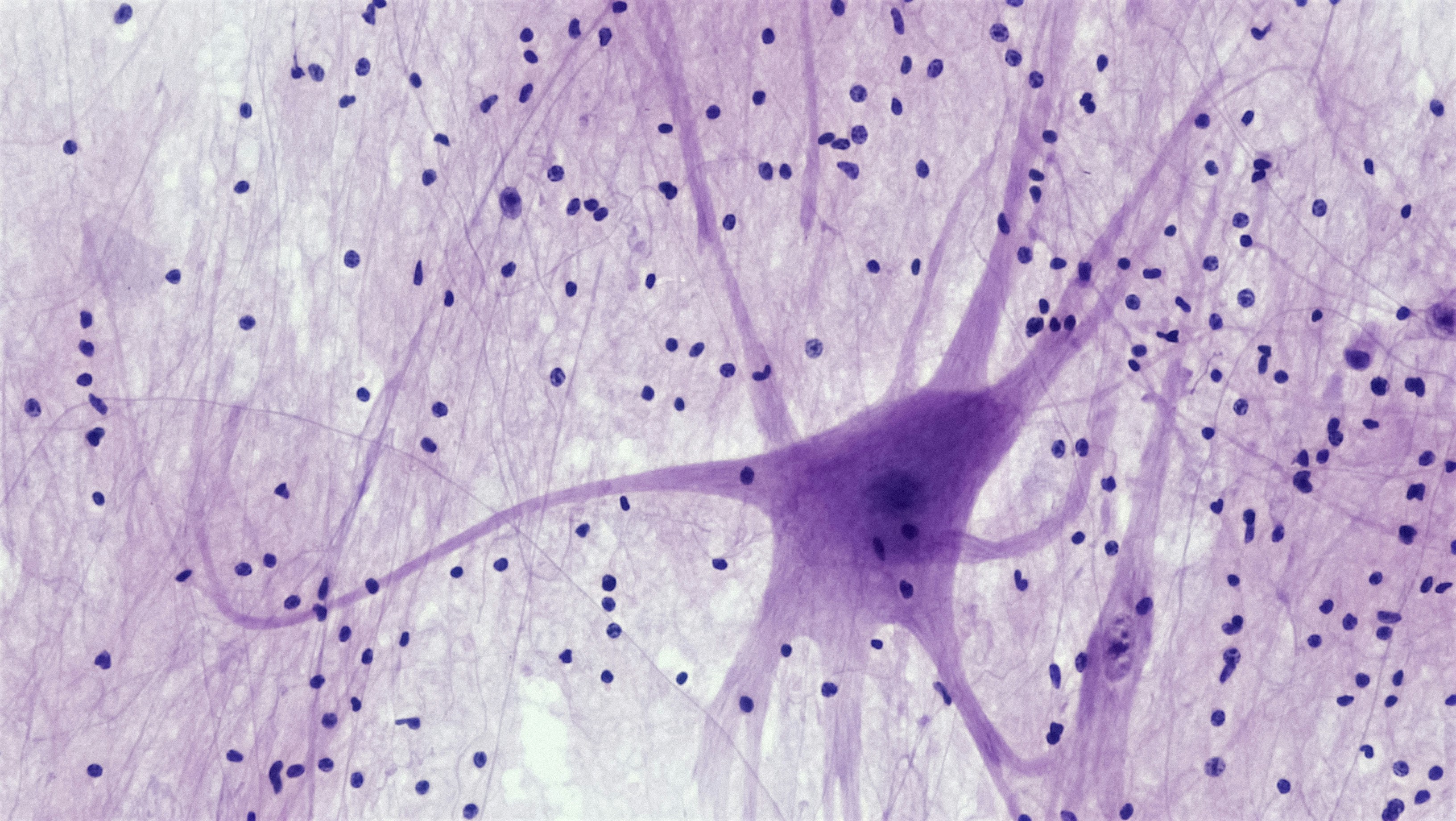

Once cocaine enters the bloodstream and crosses the blood-brain barrier, it binds to the dopamine transporter (DAT).

The limbic system — especially the nucleus accumbens, a key node of the reward pathway — is most affected by cocaine consumption. This prevents the reuptake of dopamine and results in elevated dopamine levels in the synaptic cleft, prolonging the activity of the neurotransmitter.

The unnaturally high dopamine levels in the synaptic cleft cause overactivation of postsynaptic neurons. Through intracellular signaling cascades, this leads to increased expression of the transcription factors CREB and ΔFosB. In the short term, their induction functions as a brake on reward signaling, reducing the reinforcing effects of cocaine despite the elevated dopamine.

As cocaine is metabolized and cleared by enzymes, synaptic transmission gradually returns to baseline and the acute effects wear off.

Cocaine - Reward Circuit Persistence

After consuming cocaine, several brain regions engage in a kind of tango.

The hippocampus and amygdala, both involved in storing contextual and emotional memories of pleasurable activities such as quenching thirst or engaging in sex, also encode the circumstances of cocaine use — the places, people, and sensations tied to the drug. These memories become powerful cues that can reignite craving long after the last exposure.

With repeated exposure, what begins as desire gradually turns into compulsion. Cocaine use evolves along a spectrum: the more frequent the consumption, the more automated the behavior becomes, and the less it feels like a conscious choice.

The prefrontal cortex, normally responsible for planning, weighing options, and resisting impulses, becomes increasingly overpowered. As the addictive hijack advances, control shifts from reflective decision-making to reflexive responding.

The user slowly moves from the driver’s seat to the passenger’s, watching the substance reshape the brain in ways that sustain persistence.

Next, we will see which molecular events drive this structural shift — and how cocaine escalates its influence down to the level of gene expression.

Cocaine - Privilege Escalation via Gene Expression

As we have seen, cocaine’s effects extend beyond acute signaling to the level of gene expression — most notably through the induction of ΔFosB.

This transcription factor acts as a molecular pace-setter: it regulates clusters of genes and persists for weeks before breaking down. With repeated cocaine consumption, large amounts of ΔFosB accumulate inside the nucleus accumbens, the brain’s reward hub.

“One of the genes stimulated by ΔFosB is an enzyme, cyclin-dependent kinase-5 (CDK5), which promotes nerve cell growth.”2

This means that cocaine consumption indirectly triggers the upregulation of genes such as CDK5 through ΔFosB. CDK5 influences structural plasticity in neurons — in this context, not ‘healthy’ growth, but maladaptive remodeling that strengthens the circuits driving compulsive drug-seeking.

Yet, the timescale of ΔFosB alone does not explain why cravings and relapse can occur months or even years after abstinence. A key insight comes from how cocaine reshapes the physical structure of neurons in the nucleus accumbens.

Repeated exposure drives the growth of new dendritic spines, creating additional ‘input ports’ for excitatory signals — more ways for neurons to receive stimulation. This enhances the power of drug-related cues, for example when an addicted individual meets an old friend they once used drugs with Animal studies strongly implicate ΔFosB in this structural remodeling.

The result: the nucleus accumbens becomes increasingly sensitive to incoming signals from regions such as the hippocampus and amygdala. When those stored memories of drug use are reactivated, the accumbens is triggered — like a function call in a program — and the probability of that impulse overruling rational decision-making rises with each episode of use.

Even after years of abstinence, the system remains altered — a kind of backdoor implanted into the brain. Under stress or cue exposure, the probability of relapse escalates, reflecting cocaine’s long-term privilege escalation at the genomic level.

Once hardware access (the brain’s physical structure) has been altered by cocaine, other substances such as nicotine seem to work in a similar fashion — it’s basically gg.

Further reading:

https://www.euda.europa.eu/publications/european-drug-report/2024/cocaine_en

https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/cocaine#work

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2851032/

https://www.nature.com/articles/nn1143

Nestler EJ, The Neurobiology of Cocaine Addiction, PMC2851032 ↩︎

Nestler EJ (2001). Molecular basis of long-term plasticity underlying addiction. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2, 119–128. https://doi.org/10.1038/35053570 ↩︎